An act of restitution

Eighty-five years after my grandparents fled, I received a Polish passport.

Dear friends,

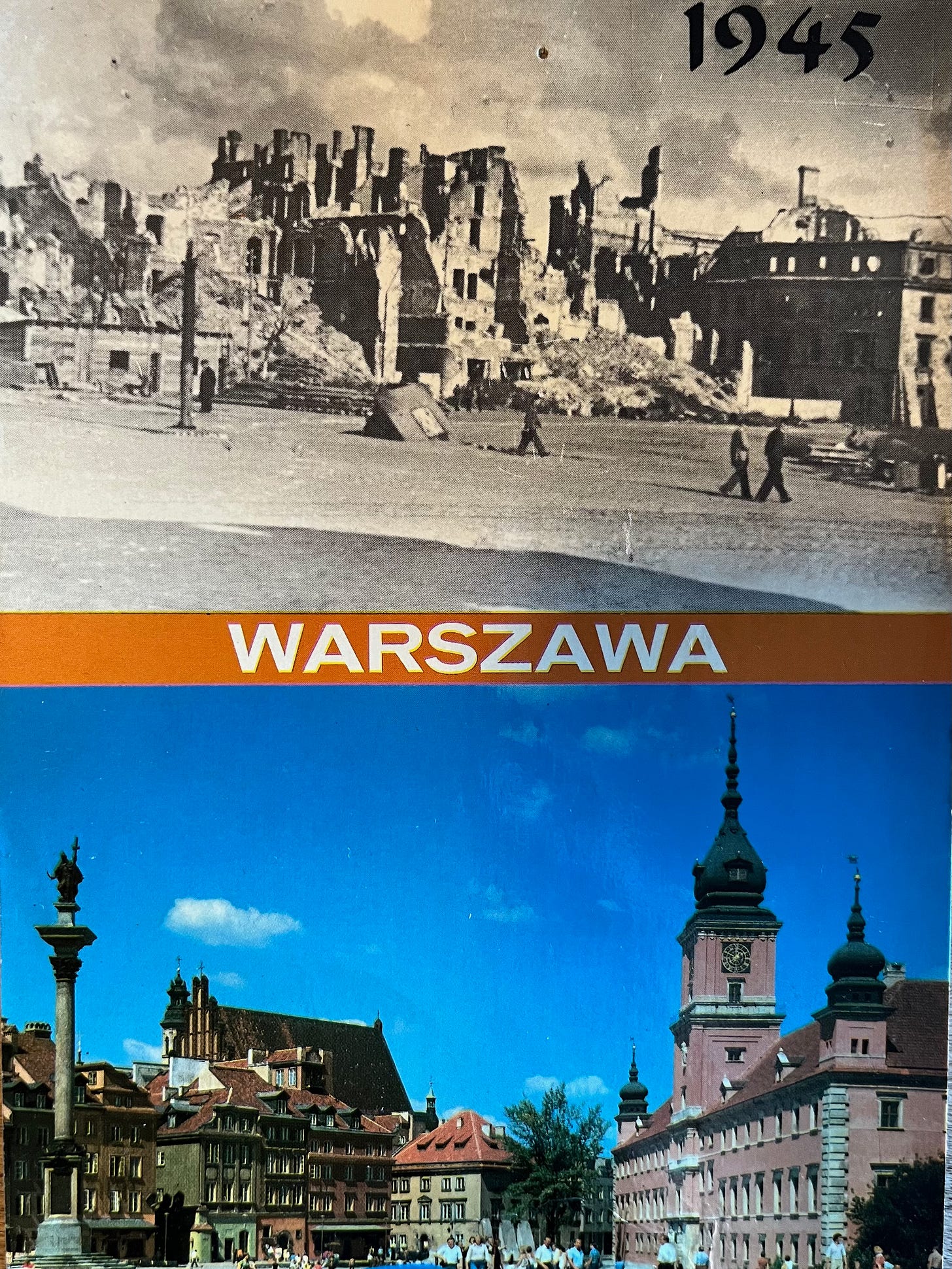

I went to Poland for the first time in 1994. During the optimistic period after the Oslo Accords, I was part of a cohort of college journalists selected to visit Israel and the West Bank and meet with leading Israeli and Palestinian figures. (It was a different time.) The trip began with a few days spent visiting Auschwitz and the former Warsaw Ghetto.

Until then, I had thought of Poland mainly as a site of trauma. My mother’s parents had been driven out of the country when Hitler invaded. Later, together with hundreds of thousands of other Polish Jews, they were deported on Stalin’s orders to a remote, freezing region of the Soviet Union. They spoke of their homeland as a place of pain and suffering.

But something happened to me in Poland that I still can’t explain. From the moment I set foot there, I felt at home. The street signs were impenetrable, filled with ł’s, ę’s, and other letters I couldn’t pronounce. Even in summer, the Warsaw cityscape looked bleak and gray. But internally I felt connected to this place in a way I had never experienced anywhere else.

The group’s itinerary marched on, but even while eating falafel in Bethlehem or visiting Orient House, the PLO headquarters in east Jerusalem (it was really a different time), I couldn’t stop thinking about Poland. When the fall semester started, I signed up for a Polish poetry class and found a study abroad program for spring. Less than six months after that fateful trip, I moved into a dorm room in Kraków.

As I’ve written before, my time there wasn’t easy. I was ready to embrace Poland, but it wasn’t ready to embrace me. Jewish culture was limited to a “Schindler’s List” tour, an annual klezmer festival, and a couple of restaurants serving unrecognizable versions of traditional foods. My Polish grammar teacher insisted that the language spoken by Jews was called “Jewish” rather than Yiddish. I was thrilled to find a summer internship at the Warsaw bureau of the New York Times, but one of my assignments was investigating a report that a flea market vendor was selling “authentic soap” manufactured at the Stutthof concentration camp. It was with some relief that I returned to the United States.

But the feeling that in some elemental way I belonged in Poland never left me. And when I returned in 2019 to profile Olga Tokarczuk for The New Yorker, it intensified. More than twenty years after my first visit, the country had undergone a seismic cultural shift and manifested a new openness to Jewish culture. An exhibit of prints by Polish artists on display at the Warsaw airport titled “Polish Family Album” included a portrait of a black-hatted, long-bearded Jewish man. A magazine editor suggested we meet at a hip vegan restaurant called Tel Aviv. Polish intellectuals sported t-shirts with Yiddish lettering.

Back home, I started looking into the process of Polish citizenship by descent. According to current Polish law, you can become a citizen if you have at least one direct ancestor who was born in Poland, lived there after 1920, and did not voluntarily give up their Polish citizenship. In fall 2020, I hired a Polish law firm to begin the process for myself and my eldest child. The process took longer than usual because of Covid delays and other complications, but last summer we finally received our passports. When I held mine in my hands, tears came to my eyes.

Of course, there were practical reasons for doing this. After 2016, I began to think seriously for the first time about leaving the United States. For many different reasons, I worry about the political climate here. It’s reassuring to have the option of living and working in the European Union if things take a drastic turn.

But Polish citizenship means more to me than a potential lifeline out of a nation in decline. It’s an act of restitution for the crime committed decades ago against my grandparents, who were robbed of everything they owned, forced into Stalin’s hands, and threatened with violence when they returned. It acknowledges that a historical injustice was perpetrated against my family. And it offers something valuable as reparation.

My citizenship certificate states that I hold Polish citizenship “from the date of birth.” On that long-ago trip, I was already a citizen of Poland, even though I didn’t know it yet. I could sense it in my bones.

Do you have dual citizenship? Have you thought about applying for citizenship by descent in Poland, Slovakia, or another Eastern European country? Tell us about it in the comments.

What I’m listening to

I’m late to the party with this one, but I recently discovered the podcast “60 Songs That Explain the 90s” and have been loving host Rob Harvilla’s brilliant, insane, insanely brilliant commentary on everything from Mazzy Star’s “slowcore” to Cher’s use of autotune. A new season—“60 Songs That Explain the 90s: The 2000s”—just kicked off with an analysis of a rhetorical trope featured in The Killers’ “Mr. Brightside” that had me literally laughing out loud while walking my dog. Rob: As a literary critic, I’m here if you need expert advice on anything else. Really! Call me.

What I’m writing

For the New York Times Book Review, I reviewed When We Flew Away, Alice Hoffman’s new novel about Anne Frank before the war—a fairy-tale-like account of an Anne who’s “spunky, dreamy and full of promise.”

As ever,

Ruth

Thank you for this post, Ruth. My experience isn't connected with one of the countries you've mentioned, but yes—I have reclaimed German citizenship. Your essay prompted me to re-read one of mine on the subject (originally published 1997), and I'm now reflecting on the further evolution of my attitudes toward my citizenship, and Germany, since I first wrote it. The essay is linked within this post (itself already a decade old): https://www.erikadreifus.com/2014/01/wednesdays-wip-memories-my-german-passport-me/

Ruth, thank you for telling this story about your family -- I was moved to read about your reconnection to your Polish roots. I visited Auschwitz this summer with my family because I want my children to understand how so many have suffered. We are Christians and multi-generational Americans, and our family doesn't have the same stories to tell. I wrote an essay about our experience that's on my Substack and thought you might enjoy reading it. https://katesusong.substack.com/p/is-anything-worse-than-this-election?r=2iyrll