Heart of Darkness revisited, etc.

Dear friends,

Not long ago, my then-fourteen-year-old’s English teacher told me that he wished he could assign his students Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad’s classic novel about the depredations of imperialism, but he felt unable to. In the current political climate, he told me, the novel is “unteachable.”

At the time, I found this approach cowardly, even though I understood—or thought I did—why the novel is so controversial. In 2008, I had written a piece for The New Yorker about the Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe’s great book Things Fall Apart, on the occasion of its fiftieth anniversary. Researching that piece, I came upon Achebe’s essay “An Image of Africa,” which famously attacks Conrad as a “thoroughgoing racist” and Heart of Darkness specifically as a racist text. Unlike many critics, Achebe argues that the novel doesn’t subvert imperialist constructs—it falls victim to them, primarily through language that depicts Africans as inhuman. The Blacks in the text are nameless and faceless, their speech barely more than grunts; they are said to be cannibals.

I read Achebe with surprise. I didn’t remember any of my English teachers, in high school or college, commenting on the book’s racist language. I looked at some of the criticism about the novel written in response to Achebe, which usually acknowledged that he had something important to say but suggested that he was a naive reader who did not recognize the difference between the voice of Marlow, the novel’s protagonist, and Conrad as author (a distinction Achebe does explicitly make in his essay). Others excused Conrad for not rising above the prejudices of his era. In my New Yorker piece about Achebe, I devoted space to his critique, but ever since then, the question of whether the novel should continue to be read and taught has lingered for me as important and unresolved.

Cover of a Penguin Classics edition, 1995.

Heart of Darkness was one of the first books I had in mind when I proposed to the 92nd Street Y a class about the intersection of politics and literary criticism. When I finally reread it in its entirety, I was stunned to see that Achebe had actually downplayed the dehumanizing language. Far from limited to a few instances, it was pervasive throughout the novel, as is the apparently gratuitous use of what we now know as the n-word. The language, to be honest, distressed me profoundly. “It’s worse than I remembered,” I wrote to a friend.

I plunged deeply into the criticism around the novel, from a contemporaneous reviewer who wrote (unbelievably) that “It must not be supposed that Mr. Conrad makes attack upon colonization, expansion, even upon Imperialism” to critics in the 1980s, 1990s, and on who look at it through a postcolonial or deconstructionist lens. I came to appreciate how deeply ambiguous the book’s narrative strategies are—from the double frame that surrounds the central story (it’s told by an unnamed narrator who is listening to Marlow, the protagonist, tell the story of his experience in Belgian Congo) to the highly ironic language Conrad employs, full of confusions, misunderstandings, and reversals. And I eventually came to believe that it’s not Conrad who dehumanizes the African characters—it’s imperialism. The novel is describing its effects, not endorsing them. The book’s rhetoric makes use of the racist tropes of Conrad’s time, but it uses them for its own purposes.

The current Norton Critical Edition. How times have changed!

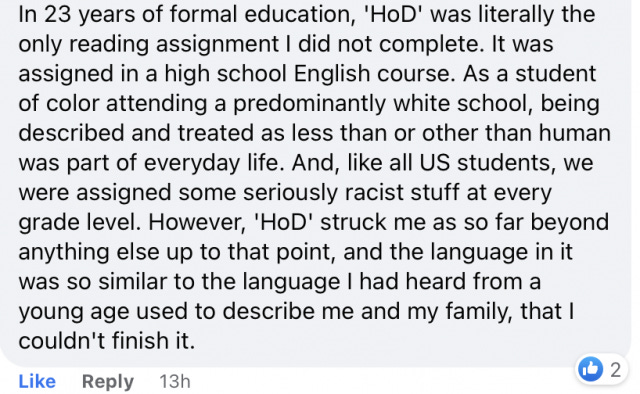

No complex book can be fully grasped on the first encounter, but Heart of Darkness is especially prone to be not just incompletely understood but misunderstood. It took me many hours of deep engagement with the text and its interpreters to reach my current understanding of it—an understanding that could potentially change on my next reading, if I see something that I missed earlier. Students who read the novel in the classroom should do so with historical context and alongside texts by African writers—a labor-intensive endeavor that isn’t available to many, and probably isn’t an option for my teenager’s NYC public high school teacher. Otherwise, they may react as this friend of mine did. Here's his comment to my Facebook query about whether the novel should still be taught:

Only one thing about this rich, ambiguous, unsettling book finally seems clear to me: the impossibility of making definitive statements about its message. “It’s not about racism,” said one person who commented on my Facebook post. It’s about “human darkness as represented by racism,” said another. A third: it’s about “a violent clash of radically different worlds.” And so on. This is probably what Conrad intended. “It was the very basis of Conrad’s work that the fable must not have the moral tacked on to its end,” the novelist Ford Madox Ford wrote in a memoir of their friendship. And it’s part of what has made the novel so enduring. Like Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” another work of fiction that has been subject to all kinds of political interpretations, it’s a parable that can be applied under many different circumstances.

More than anything else, I wanted my 92Y students to see that there is no easy answer to the question of whether a book like Heart of Darkness—a masterpiece in many ways, but with language that can be very difficult to handle—should remain in the canon. “I wince at the question even having to be asked,” one of my commenters wrote. I don't see asking the question as a symptom of cowardice or submission to “wokeism.” Rather, it's an acknowledgment that the world has changed in important ways in the last 100 years, and that our literary and cultural values, too, must constantly evolve.

Where I’ll be

The next installment of my 92Y course will be March 17. The book is To Kill a Mockingbird, which has come under fire as emblematic of the white savior complex. Sign up here. As I did this month, I'll host a conversation about the book's politics in advance on Facebook and Twitter.

What I’m reading

I recommend the Norton Critical Edition of Heart of Darkness for its wealth of historical documents and critical commentary and Maya Jasanoff’s The Dawn Watch: Joseph Conrad and His World, a brilliant and in depth biography/historical study. The director’s cut of Apocalypse Now (Coppola’s transposition of the story to Vietnam) is streaming on Netflix. And with my teenagers, I’m rewatching Lost—another depiction of monomania in the jungle.

Want to tackle The Books of Jacob but worried about how long it will take? Find out in advance with this handy Olga Tokarczuk Books Calculator. I love that someone made this. Now if I only had a calculator to help me figure out how long it will take to write things ...

As ever,

Ruth

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are considered, by some, to dream.”—Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House