Friends, I have done it. A rash, tedious, long-overdue project that I never thought was possible.

I have Kondo-ed my books.

I’ve been writing book criticism for twenty-five years. Twenty-five years as a book critic means a lot of free books. In the post-Covid period, many publishers have shifted to e-galleys, a reprieve welcomed by both my sagging shelves and my husband, who for years has gamely tolerated the piles stacking up in virtually every corner of our house. Even so, the thump of a book being tossed on the porch is so familiar that our dog doesn’t even bark at it.

It’s a privilege and a pleasure to own so many books. My husband and I chose our house, an aging Victorian on the southern edge of Flatbush, mainly because of its ample space: for the children and pets we would raise there, yes, but also for my books.

But at the end of the summer, as we made the decision to downsize our possessions, I realized it was time to ask myself some hard questions about what purpose all those books were serving. And so I went through them, one by one.

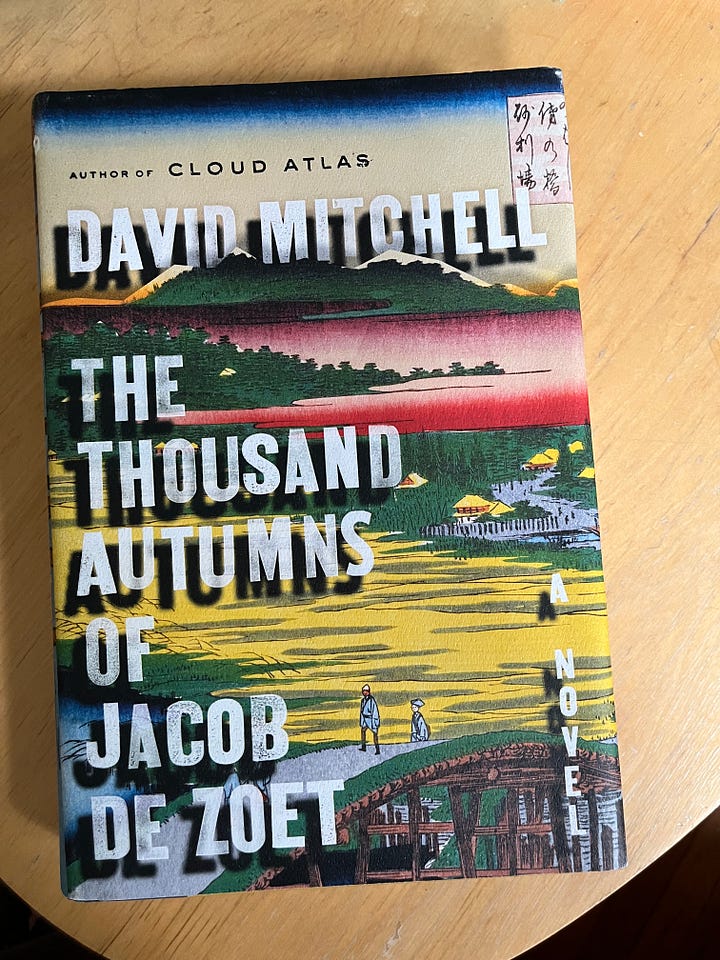

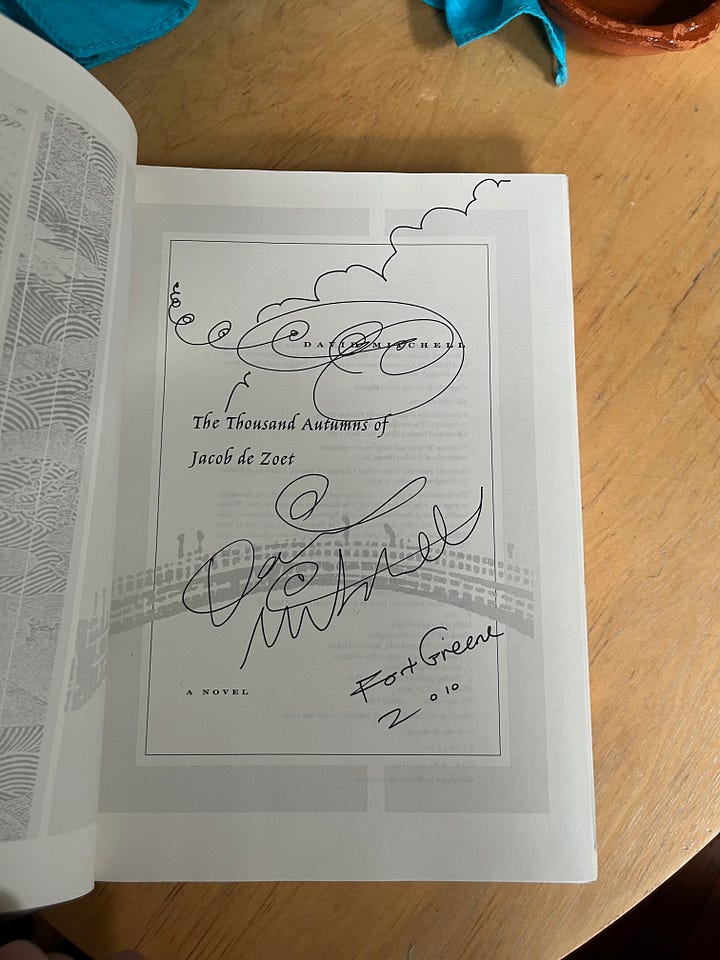

The bookshelves were a map of my taste and its development. The high school leftovers, some (Jude the Obscure) more cherished than others (The Fountainhead); the obsessions of my twenties and thirties (entire shelves devoted to W.G. Sebald, Primo Levi, Alice Munro, David Mitchell, and more); the books around which I built my own three manuscripts and the ones I used to teach a dozen years’ worth of university classes in journalism, criticism, and biography—these were the raw materials of my intellectual life. No wonder it felt so important to have them as close as possible to hand.

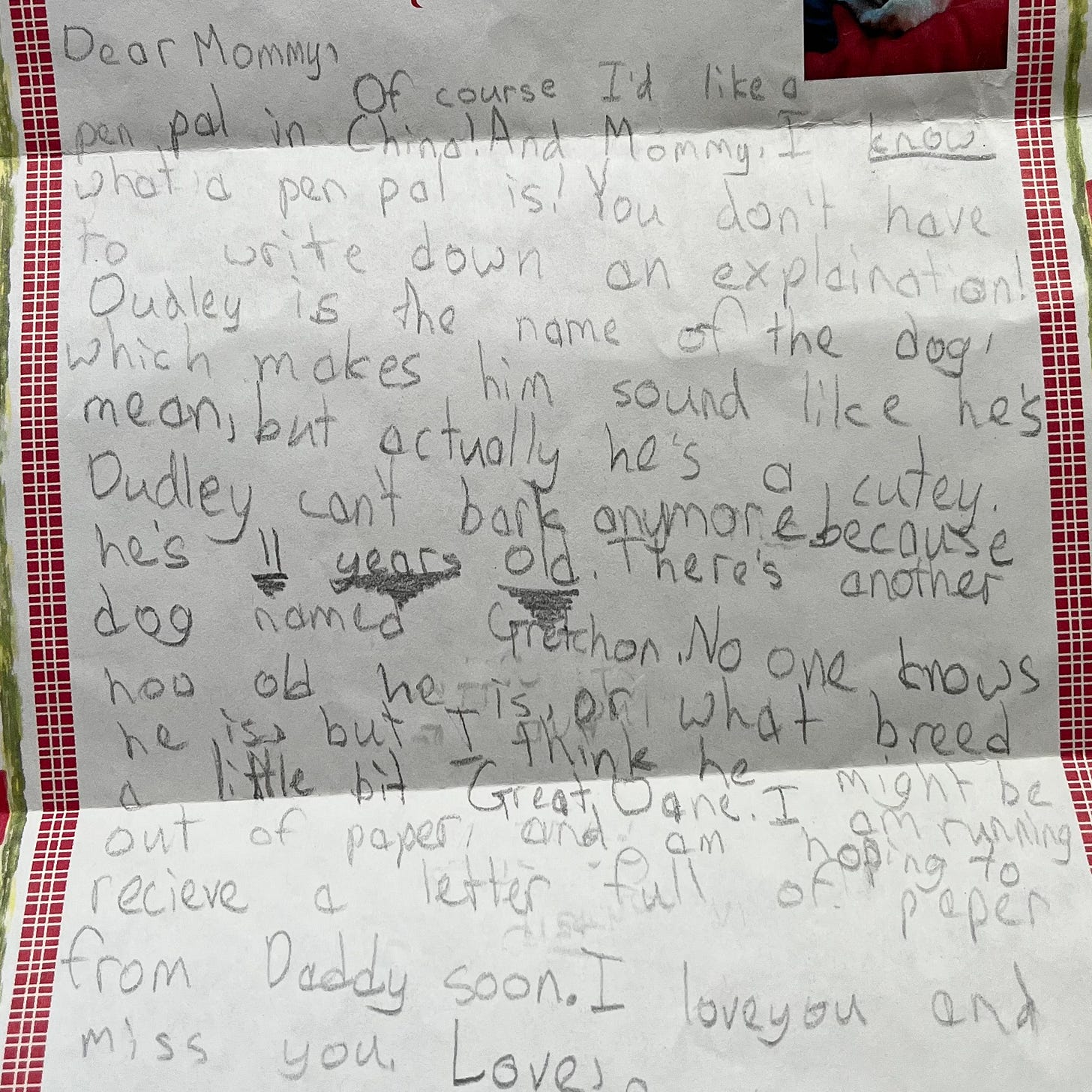

They were also a secret diary that only I could read, dotted with ephemera collected over the decades. In an edition of Ovid’s Erotic Poems, I discovered a note passed to my fifteen-year-old self by a shy, silent boy in my driver’s ed class, asking me to “excuse this primitive manner of introduction” and to drop by his house, if I had time. (Erotic poems? No wonder he was interested.) D.H. Lawrence’s The Rainbow, which I read once in college and never again, still held a Hanukkah card signed by my father and stepmother, now divorced for nearly two decades. A list of street addresses (!) of friends and family members to whom to send postcards (!!), found in a novel by Graham Greene, brought me back to a stay in Berlin that happened to coincide with one of my first pieces for The New Yorker: a review of a biography of Greene, well before I thought about writing biography myself. Berlin was under a heat wave and I was heavily pregnant with my first child, so I spent most of my time there floating in the lakes and reading Greene’s novels. A decade later, I stuck a letter from my middle child into a book of criticism by Stanley Edgar Hyman, read during a residency at Macdowell—precious time to focus on my Shirley Jackson biography while the kids were at sleepaway camp.

But this shelf-level perspective on my personal history also revealed how much I had tried to shape myself according to the tastes and expectations of others. Foremost among them was my charismatic, abusive former boss, who used to put notes, mostly on Post-Its and always signed “Love,” in the many books he left on my desk for my edification. To my surprise, I found myself putting most of them in the giveaway pile.

Once I started, I couldn’t stop. An obscure Italian novel that I never managed to read, beloved by a literary critic whom I once idolized? In the pile. Several volumes—signed, naturally—by an older poet with whom I had a mercifully brief entanglement? Out. The chapbook of comically unreadable sonnets by a British exchange student I met in graduate school? (That one I kept, a souvenir of my years among the sad young literary men.) The first novel I ever reviewed for The New York Times also got to stay—but not the six previous ones by the same author that I diligently consumed in preparation.

Books seem so permanent, but they don’t last forever. I wanted to keep two mass-market paperbacks of Animal Farm and 1984—God knows, I might need them—but their pages were so musty, brown and crackling, that I put them in the giveaway pile. Same with the dual edition of Howards End and A Room with a View, purchased in tribute to Merchant Ivory—I read the books, but I loved the movies more—and another of Middlemarch, with a postcard from Costa Rica placed as a bookmark about two-thirds of the way through. The trip was in 2008, an attempt at a family vacation during the death throes of my first marriage. Apparently that was enough to put me off finishing Middlemarch. The book went in the free pile, with the postcard still in it.

Anne Helen Petersen and others have written about the phenomenon of the “portal”: a spiritual, emotional, or creative crossroads that women may reach in midlife.1 The term came back to me as I stood amid all those volumes offering mute testimony to the journey of my mind. Am I able, now, to let go of them because I am now 51, the author of three published books and dozens of essays, and finally beholden to no one’s ideas but my own? Or was the process of sorting the books—taking each one into my hands, paging through it, and making a decision about whether I still needed it or not—itself a necessary step in understanding which aspects of my history I am ready to leave behind?

Have you ever gotten rid of something that once was important to you—books, clothes, memorabilia, or something else? What prompted you to do it? How did it feel? Let me know in the comments.

What I’m reading

Maggie Millner’s essay in the Yale Review about Mary Oliver and shame has a fresh and very convincing take on Oliver’s best-known lines: “Tell me, what is it you plan to do / with your one wild and precious life?”

Late to the game, but Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s novel Fleishman Is in Trouble gave me a lot to think about.

Where I’ll be

Two in-person events are coming up:

November 2, New Haven, 7 p.m.: In conversation with Joshua Cohen on “Jews and Publishing Today,” as part of a conference sponsored by the Yale Program in Jewish Studies. Register here.

November 3, Toronto, 7:30 p.m.: In conversation with Heather Reisman of Indigo Books and Music for opening night of Holocaust Education Week at the Toronto Holocaust Museum. Tickets here.

And one online:

November 16, 12 p.m. EST, I’m offering a class called “Better Writing Through Criticism” via the Shipman Agency’s popular Work Room. It’s a craft seminar on using criticism as a technique for personal essays and other writing. Three scholarships are available. From the description:

How can thinking and writing critically about art and culture deepen our practice as creative writers? Join Ruth Franklin, a longtime book critic and teacher of nonfiction, to consider how works or art to which we are drawn—paintings, books, film, photographs—can give us new ideas for or perspectives on our own work. In this single-session class, we'll do a close read of a short lyric essay that blends criticism and memoir. We'll then practice some techniques to accomplish similar effects and discuss strategies for responding to the art we consume on a daily basis, from books and museum exhibitions to podcasts, television, and more.

As ever,

Ruth

These lines especially resonate: “The experience is more intense if you’ve been heads-down — absorbed by parenting, by your career, by an illness, by something — for some time.”

I got rid of 50 boxes of books because my wife and I were moving to assisted living. She has alzheimers and needed more support than I could provide myself. She's now in memory care, and I'm living in an apartment. I miss my books! I didn't think I would, because I reserve books at the library all the time. But it's hard to have to postpone the impulse to look something up, or to re-read.

You're stronger than I am, Ruth! Just moved into a new house to start a new life and decided to buy extra bookcases and unbox every book I could... parting with them is a fate too terrible to contemplate.