Welcome to my new subscribers! I’m glad you’re here. This email comes out monthly. In the meantime, find me on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

What I’m writing

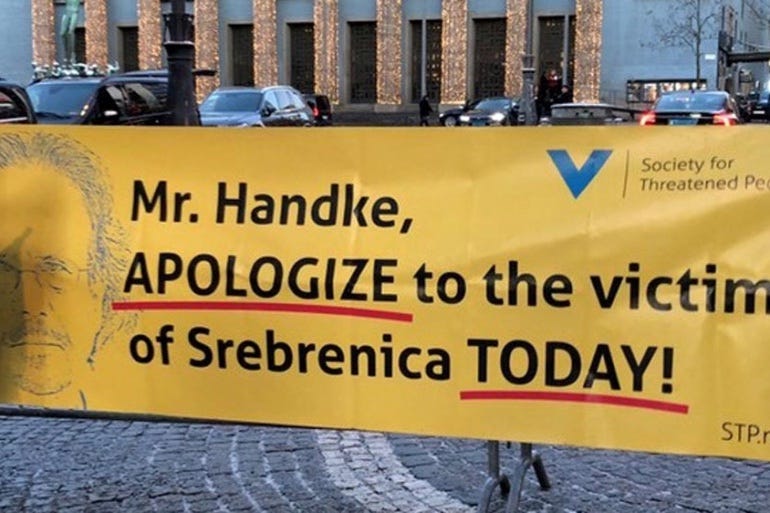

When the Austrian writer Peter Handke was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2019, I got into an argument with a journalist friend who had covered the Balkan Wars. My friend was furious that Handke, who made his name in the 1960s and 1970s as an experimental novelist and playwright but has recently become much better known (at least in certain circles) as an apologist for Slobodan Miloševic, had received the ultimate literary honor. Shouldn’t his politically reprehensible writings disqualify him?

Well, in a nutshell, not necessarily. The prize in the past has gone to writers of all political persuasions. As Bret Stephens pointed out in this column, Sartre visited the Soviet Union in 1954 and praised its “complete freedom from criticism.” Günter Grass turned out to have been a member of the Waffen SS. García Márquez cozied up to Fidel Castro. By this standard, it would be unfair to take Handke to task for his political missteps, however grave they might be.

That’s what I thought before I immersed myself in Handke’s work. If it’s ever entirely possible to separate a person from their creative labors—and I’m growing less and less convinced that it is—it’s especially difficult with regard to Handke, whose fiction and nonfiction utilize the same narrative strategies and embody the same intellectual philosophy. As I concluded in this piece for The New Yorker:

“Rather than a departure from his literary work, Handke’s position on Serbia may be of a piece with it—a logical consequence of the postmodern experimentation for which he has long been celebrated…. The idea that the facts of a situation can be whatever we say they are sounds different now from the way it may have thirty or forty years ago. Some realities—the mass graves at Srebrenica, or, more recently, the outcome of an election legally conducted—cannot be treated ‘dialectically.’ ”

I filed that piece just before Putin’s attack on Ukraine. I’d now add to that list: a war waged by a country whose citizens are forbidden to call it an “invasion.”

Where I’ll be

As regular readers of this newsletter know, I’ve been teaching a course examining the intersection of politics and literary criticism at the 92 St Y (on Zoom). I called it “Can This Novel Be Saved?”, but as I get deeper into this morass, I realize more and more that the question isn’t so much to decide whether certain beloved novels “deserve” to be canceled, but to define the stakes that determine why some books endure in the canon despite (or because of) their retrograde politics. Last month we looked at Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, which has been justifiably criticized for its white-savior plot as well as its generally reductive depictions of Black people. Does the novel re-enact the racist milieu that it depicts, or does it manage to rise above its own political circumstances? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

The next and last class in the series is April 14, on Lolita. Sign up here.

What I’m reading/watching/listening to

I’m watching Lost with my teenagers: their first time, my second. In an effort to cover up the fact that I’ve forgotten a shocking number of the salient details, I’ve been immersing myself in The Storm, a rewatch podcast that so far has taken on Star Wars, Game of Thrones and Lost. The show’s structure is ingenious: the first half, “The Calm,” is spoiler-free and safe for newbies; the second half, “The Storm,” goes all out. I also love the sharp banter among the show’s hosts: Joanna Robinson, Dave Gonzales, and Neil Miller. They’ve now moved on to a new podcast, Trial By Content.

As ever,

Ruth

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are considered, by some, to dream.”—Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House

Enjoyed this!