The diaries of Anne Frank

Why is a basic fact about the most beloved work of Holocaust literature so little known?

Welcome to my new subscribers! I’m glad you’re here. This email comes out once a month. Otherwise, find me on Twitter, Instagram, or (if you must) Facebook.

What I’m writing

I’ve entered into an intense writing phase, hoping to finish my book about Anne Frank—or most of it, anyway—by the end of the summer. I jump-started this process in early June with Jami Attenberg’s #1000wordsofsummer, which I highly recommend. She’s running a mini-version in August.

I haven’t been able to hit 1000 words every day since then, since I’m balancing the writing with research, including trips to Columbia’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Library to read through Otto Frank’s correspondence with his editors at Doubleday and to the Center for Jewish History for letters relating to Otto’s efforts to get the family to the United States in 1941, when it was still—just barely—possible for Jews to escape from Holland. Otto sent heartbreaking letters to Nathan Straus Jr., a close friend of his from their university days at Heidelberg, who was then working in the FDR administration. The U.S. immigration system was so byzantine that even Straus and his wife, confidants of the Roosevelts, had trouble navigating it. They were working on getting Otto to Cuba when the U.S. entered the war and canceled his visa. You know the rest of the story.

In my last newsletter, I mentioned that many facts about Anne’s life are unknown and always will be, including her date of death. But there’s an important fact about her that should be widely known—and yet it’s not. Anne herself edited her diary for publication, long before her father supposedly censored it (as many have claimed). Here’s the story.

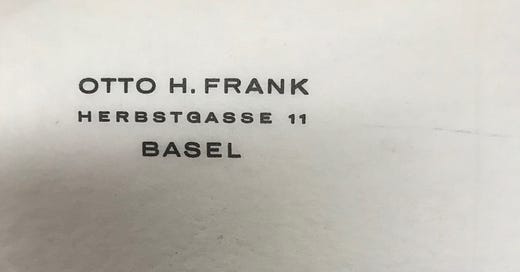

On March 28, 1944, at around 7:30 in the evening, the residents of the Secret Annex were listening to Radio Orange, the broadcast service of the Dutch government-in-exile in London, when Gerrit Bolkestein, minister of education, arts and sciences, came on to deliver a special address announcing the planned creation of a national archive of material relating to the war years.

After the war, Bolkestein announced, the government planned to establish a national center to collect, edit, and publish “all historical material relating to these years.” It might include editions of Dutch underground magazines, records of the resistance, and so forth. “I am calling on all listeners,” he said:

History cannot be written solely on the basis of official records and archives. If posterity is to fully understand what we as a people have endured and overcome in these years, we must collect an enormous amount of material relating to daily life. Only then can this struggle for freedom be depicted in its full depth.

Of course they all made a rush at my diary immediately, Anne recorded the next day. Her thoughts went immediately to reworking it into a romance—that is to say, a novel—of the “Secret Annex,” although she worried that people would think, based on that name, that it was a detective story. But, seriously, it would be quite funny 10 years after the war if people were told how we Jews lived and what we ate and talked about here.

“If people were told”—that’s Anne’s original version. Returning to it a few months later, she made a small but significant revision: But, seriously, it would be quite funny 10 years after the war if we Jews were to tell how we lived and what we ate and talked about here. The story of persecution couldn’t be told by others. Those who had lived it would need to tell it themselves.

Although I tell you a lot, still, even so, you only know very little of our lives, Anne reflected, addressing her diary in the second person, as was her practice. The idea that others might read what she had written made her conscious of all the things she had left out, such as how frightened the women in the house were during the air raids: when the British dropped bombs on the port town of Ijmuiden, 35 kilometers away, windows rattled in Amsterdam. Or the epidemics raging in the city; the long lines for vegetables and other necessities; the rampant thefts and burglaries, even by children. I would need to keep on writing the whole day if I were to tell you everything in detail.

And so she went back to the beginning and started over: rewriting her entries, adding new ones, deleting others, substituting pseudonyms for names. She had decided that she was going to publish this book—she would call it Het Achterhuis, “The House Behind,” or, as her hiding place has become known in English, “The Secret Annex”—after she was free.

After the raid on the Secret Annex, Miep Gies and Bep Voskuijl, two of the office workers who had sustained the Franks in hiding, found Anne’s papers scattered on the floor and saved them. When the news came that she had died, Miep gave the pages to Otto with the words, “Here is your daughter Anne’s legacy to you.”

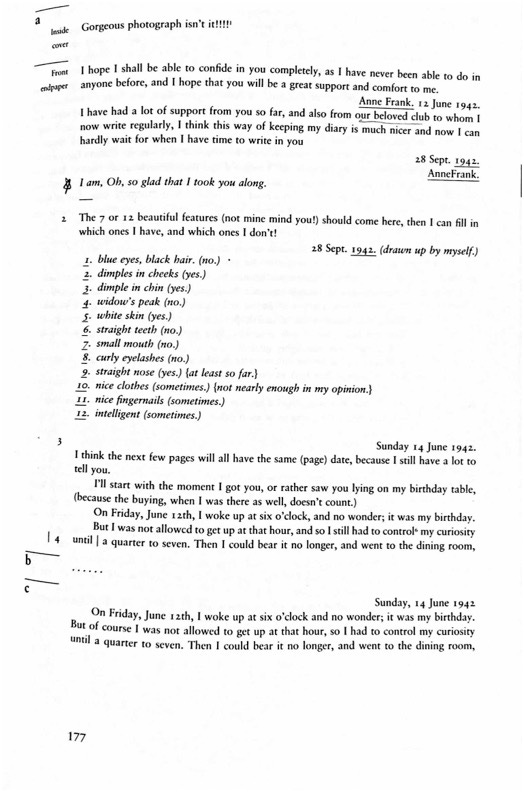

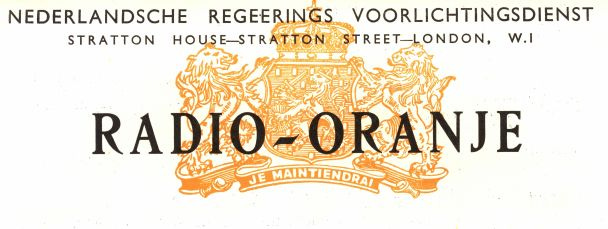

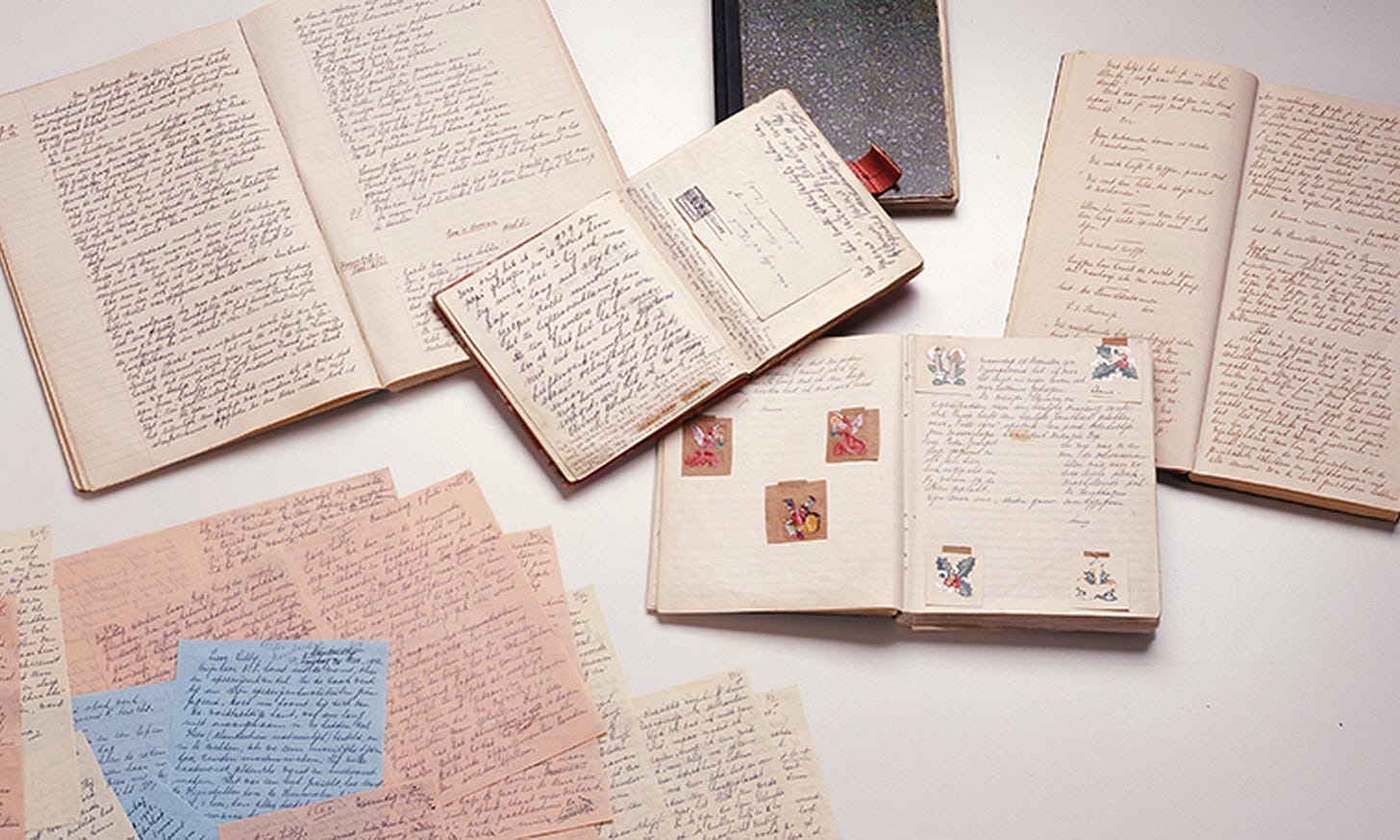

Otto knew the book should be published, but he wasn’t sure how to make a readable text out of the two versions. He couldn’t publish only the first, unrevised diary—in part because a big chunk of it was missing. Anne’s first diary, kept in a red-checkered notebook, covers the period from June 12, 1942 to November 13, 1942. Two other notebooks have been found: one from December 22, 1943 to April 17, 1944; another from April 18, 1944 to August 1, 1944. The originals for the interim period—November 1942 to December 1943—are presumably lost. Moreover, Anne’s voice had changed over those two years in hiding. The first version largely reads like the diary of a schoolgirl. The second is written in the voice of Anne that the world now knows: polished, thoughtful, mature.

But he couldn’t publish only the second version, either. First of all, Anne likely hadn’t finished recopying and rewriting it. More to the point, she had removed things that Otto felt should be left in—particularly her romance with Peter van Pels, which brightens the diary’s atmosphere during the late winter and spring of 1944. The romance quickly ran its course—primarily, it seems, because Anne grew bored with Peter, who wasn’t as introspective as she was—and she may have found the memory of it embarrassing. Nonetheless, Otto chose to override her, a decision that reveals his instinct for a good story.

Contrary to popular belief, it was Anne, not Otto, who cut her thoughts about menstruation (Each time I have a period—and that has only been three times—I have the feeling that in spite of all the pain, unpleasantness, and nastiness, I have a sweet secret) and the now notorious passage in which she recalls asking to touch a girlfriend’s breasts during a sleepover. It was also Anne who cut references to Judaism, such as a mention of observing Yom Kippur in the Secret Annex (There can’t be many people who will have kept it [the holiday] as quietly as we did). Otto did remove some of her harsher remarks about her mother and Mrs. van Pels, perhaps assuming, reasonably, that if Anne had known that they would die in the camps, she wouldn’t have wanted them to be remembered in those terms.

So there are initially three versions of the diary: version A, Anne’s incomplete original; version B, her (likely also incomplete) revision; and version C, Otto’s edit, first published in Dutch in 1947 and in English in 1952. The existence of these versions has been well known since 1986, when the Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation—the institute that Bolkestein envisioned in his address to the occupied nation—published The Diary of Anne Frank: The Critical Edition, which lays them all out, to the extent possible, entry by entry. (Complicating matters somewhat, in 1995 a new “Definitive Edition” was created by Mirjam Pressler, the diary’s German translator, which expands on version C by incorporating material from version A.)

Why does this matter? To begin with, Otto Frank has been bizarrely and unfairly vilified as the censor of Anne’s diary, when in fact he was nothing of the kind. But it’s also important for historical reasons. In an entry dated October 9, 1942, Anne discusses what she and the others knew about the fate of the Dutch Jews who were being deported: “We assume that most of them are murdered. The English radio speaks of their being gassed.” Some historians have pointed to this entry as evidence that Dutch people at the time knew of the existence of Auschwitz. But Anne added the line about gassing in version B, meaning that it was written after March 1944 and probably as late as May or June, and can’t be relied on as a source for fall 1942.

Finally, the edits are important because they affect the way we understand Anne and her final creation, which wasn’t a conventional diary per se—a series of entries written in chronological order—but, as Francine Prose has described it, “a memoir in diary form.” In reworking her book from a private text into a public one, she transformed it from an intimate chronicle of her thoughts and feelings into a text of witness: one written by a Jew who wanted the world to know of her persecution by the Nazis. (But, seriously, it would be quite funny 10 years after the war if we Jews were to tell how we lived and what we ate and talked about here.) It wasn’t a “found object,” as some critics have assumed, but a testimony deliberately composed. To suggest otherwise misunderstands Anne’s intention and denies her agency.

In the time I’ve spent working on this book, many people have asked me variations on the same question: What is there left to say about Anne Frank? Almost invariably, they’re surprised to learn that she revised her own diary. Why, despite all the evidence to the contrary, does this misunderstanding of her work persist? I’m curious to hear your thoughts.

What I’m reading

It’s pretty much “all Anne Frank, all the time” around here, but I did make time for this fascinating translation of Mexican novelist Yuri Herrera’s novellas, complete with translator Lisa Dillman’s commentary on Herrera’s language. The last novella in this collection, On the Transmigration of Bodies, is a pandemic novel … written in 2013.

Elsewhere on Substack

I’m loving Deborah Copaken’s Ladyparts, a sharp and unforgiving take on life in America as a middle-aged woman (ask me how I know!). Her memoir, by the same name, will keep you up at night.

From the Shirley Jackson files

The New Yorker just published “Call Me Ishmael,” Jackson’s brief, strange first story for Spectre, the college literary magazine she edited with her husband, future literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman. I’ve been trying to picture what Jackson would have thought if she could have known that after all this time it would appear in The New Yorker, which rejected every single piece of fiction she submitted after “The Lottery.” It’s an irony worthy of a Shirley Jackson story.

As ever,

Ruth

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are considered, by some, to dream.”—Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House

A few reasons I think that the misunderstanding persists:

1. Anne was a good writer! So she did a good job of putting together a convincing document that seems authentic as a found object. Of course it is authentic, but it's also, as you explained, very intentional.

2. Fake found manuscripts are the genesis of the novel in many ways. We feel better about believing something that we read when we think "no one was supposed to even read this!" When we know it has been created intentionally for consumption, we feel manipulated in some way. And so we become skeptical. We don't want to be skeptical about a girl forced to live in hiding and ultimately killed by the Nazis, so we assume that the most correct assumption is the simplest.

3. Innocence is such an important piece of how people respond to Frank's diaries. The idea of her as an innocent child is so important. Her own revisions and thoughtfulness about how her diary might be understood undermines her position as a child (even though of course she still was an innocent child--she was also a really smart one).

I don’t know what the situation is now, but it used to be that, in many schools, some form of Anne Frank’s diary was the sum total of what passed for middle school Holocaust education. Girls related to it as expressing their desires, frustrations, and irritations with adults, siblings,and particularly their mothers. Boys tended to be unaffected by it , if not disliking it, for the same reasons. It all cases, Judaism and the Holocaust were barely visible, if at all, which is why Anne Frank is so many people’s favorite- if not only- Holocaust victim.