Updates from the Shirley Jackson files, #11

Dear readers,

Thanks to those of you who wrote in response to my query, I now have many questions about Shirley Jackson to answer in future newsletters. But now it’s hot, and I feel languid and out of sorts, and perhaps you do too. So I want to tell you a story about something that happened while I was working on this book.

Last summer, while the kids were at camp, my husband and I spent a few weeks in Bennington, Vermont. Friends had found us a lovely house whose owners needed someone to look after their garden while they were on vacation. In return, we got a respite from New York and some secluded writing time. And of course, for me it was a bonus to be in Shirley Jackson country—to spend time with two of her children, who still live near there, and just to soak up the atmosphere.

The catamount, a type of mountain lion, is the town symbol, as my husband noticed when we drove in. A runner who likes to head off-trail, he wondered whether there had been any recent sightings in the area. I assured him that they were rare. But on one of our first days in town, he returned from his run looking nervous. He had gone exploring, he said, and discovered a path into the woods, but decided not to pursue it. When I pressed him, he said he had been afraid of meeting a catamount.

I laughed. But I also wanted to see for myself. That afternoon I headed in the same direction.

The house we were staying in was in Old Bennington, just down the road from the campus of Southern Vermont College. I entered the grounds and went up a small hill, then started across a wide field. The grass was unmown; it came nearly to my knees in places. The path that cut through it was so narrow that I had to place one foot in front of the other. As I followed the path up through the field toward the thick woods on the other side, I felt a growing unease.

A scene from The Haunting of Hill House came to my mind. Early in the novel, Eleanor and Theodora run across the lawn and follow a little path through the trees to a brook. As they lounge there, telling jokes and stories, they see, or think they see, something in the grass.

Frozen, shoulders pressed together, they stared, watching the spot of hillside across the brook where the grass moved, watching something unseen move slowly across the bright green hill, chilling the sunlight and the dancing little brook. “What is it?” Eleanor said in a breath, and Theodora put a strong hand on her wrist.

“It’s gone,” Theodora said clearly, and the sun came back and it was warm again. “It was a rabbit,” Theodora said.

Notice the musicality of that first sentence. Watching the spot … watching something unseen … chilling the sunlight and the dancing little brook. If you’ve heard the recording of Jackson reading “The Lottery” and “The Daemon Lover”—and if you’re a Jackson fan, you absolutely must!—you can imagine her voice reading it. A lesser writer couldn’t get away with a phrase like “watching something unseen,” on its face an absurdity. How can you watch something that remains unseen? How can something remain unseen, even as you watch it? That, in a phrase, is the paradox of Hill House.

As I stood on that hill in the blazing afternoon sunlight, the grass waving slowly around my legs, I too felt a chill. Before me the path led into the woods. I remembered what my husband had said about catamounts. I turned and headed back across the field, as quickly as I could manage in the high grass.

On the other side, back towards the college, I found another path. The woods weren’t quite as dark here, and I followed it along an old stone fence. When it opened into a clearing, I gasped. I recognized the building in front of me. I had seen it once before—not in a dream, as these stories usually go, but in Jackson’s files.

Jackson’s archive, at the Library of Congress, contains numerous folders marked “Miscellany.” There are many things I could say about this archive and its system of organization—or lack thereof—but they will have to wait for another letter. For now, I’ll note only that it was in the so-called Miscellany that some of the most interesting items turned up. And one of these was a folder marked “Scrapbook.”

It wasn’t a scrapbook, but a collection of pictures and newspaper clippings. As I flipped through, I realized these were items that had inspired Hill House. There were newspaper articles about poltergeist incidents, including a case on Long Island in 1958 involving a twelve-year-old boy named Jimmy Herrmann. (You can read more about it in my book.) There was a note on religious scrapbooks annotated in blood—perhaps the impetus for the creepy book of religious teachings Hugh Crain, the creator of Hill House, makes for his daughter, which he signs in his own blood.

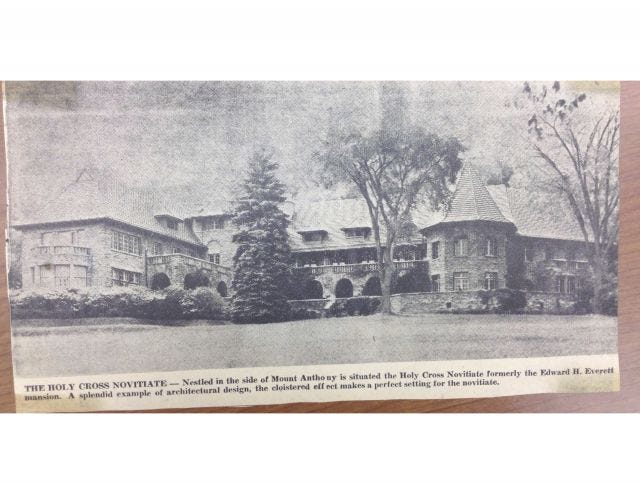

And there were pictures of houses, many of them. Neuschwanstein Castle. The Château de Monte-Cristo. The Winchester Mystery House. And a vast stone mansion, with a long verandah and a turret. The caption identified it as the Holy Cross Novitiate, formerly the Edward H. Everett mansion, “nestled in the side of Mount Anthony.” I had no idea it was in Vermont, let alone so close to Bennington. Yet there I was, on its back lawn.

The image in Jackson's files.

The mansion as it looks today.

The house took my breath away. So huge, so ugly, so evil. There was no other way to describe it. I could not be in its presence for a moment longer than necessary. I hurried around to the front and nearly ran down the driveway, which curved down a hill and came out on the main campus road, not stopping until I reached the main gate. That gate, too, was somehow familiar. Tall and ominous and heavy, set strongly into a stone wall which went off through the trees. At the top was a letter E.

What are now the grounds of Southern Vermont College used to be the estate of Edward H. Everett. There are some interesting legends about the place, including a story of disputed inheritance that may also sound familiar to some of you. A double suicide took place just outside its grounds in 1956, shortly before Jackson began writing Hill House. The mansion was owned by the Holy Cross Novitiate before it was turned over to Southern Vermont College in the early 1970s.

Both my husband and I, separately, felt something out there in the grass. More rationally inclined, he interpreted his unease about the woods as a fear of mountain lions. Did I—somewhat less rationally inclined—sense something unseen? Or did Jackson, who lived only a few miles away and must have heard the strange stories about the mansion, indeed use it as a model for the house and grounds in Hill House? In that case, what I felt were not ghostly reverberations but something almost as uncanny: the glimpse of something in real life that I had previously seen only in my imagination.

Wishing you chills in the summer heat,

Ruth

p.s. I'm aware that Jennings Hall on the Bennington College campus has long been rumored to be the model for Hill House. I wasn't able to find any evidence whatsoever for this. There's no image of Jennings in Jackson's file with the others. It's also a very different kind of building from the ones she seemed to have liked. (And, as I say in the book, there's no single model for Hill House.) But if you know of any evidence, please write and tell me!

"No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream."

—Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of HIll House