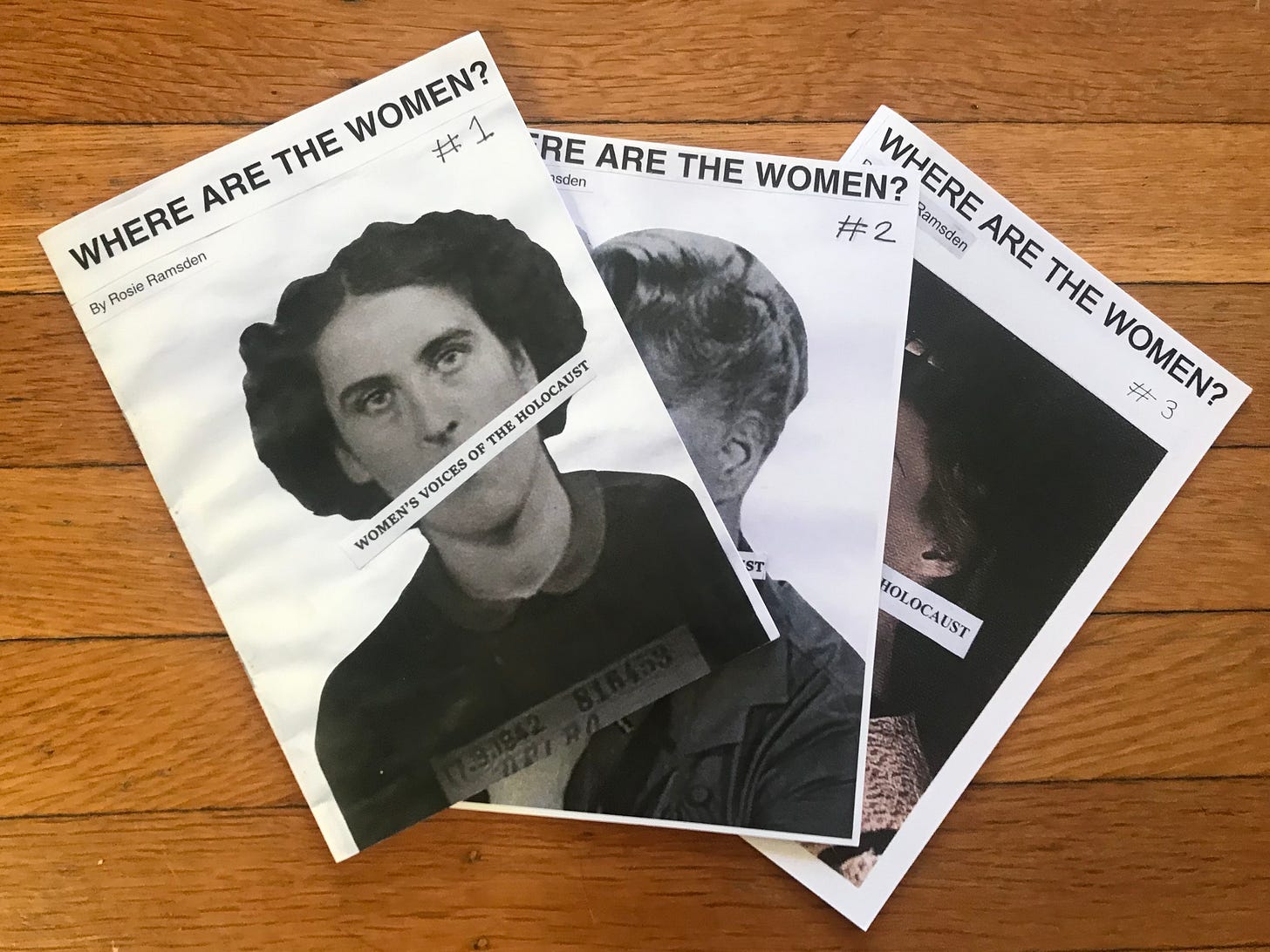

A few years ago, I came across images of a zine—yes, a zine!—online. WHERE ARE THE WOMEN? was printed in bold capital letters across the top of the cover. Below was a woman with curly dark hair and heavy brows, her Auschwitz number visible on a placard on her chest. The subtitle, “Women’s Voices of the Holocaust,” was positioned diagonally, covering her mouth.

The woman in that picture was Charlotte Delbo, a Frenchwoman who survived the camps and later published the memoir Auschwitz and After. But almost all the other women featured in the issue were unknown to me. As Rosie Ramsden, the zine’s creator, points out in her introduction, the narratives of the Holocaust are dominated by male voices, from survivor testimonies by Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi to important secondary works by Claude Lanzmann and Art Spiegelman. But with the exception of Anne Frank, whose diary ends before her imprisonment in Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, the voices of female victims and survivors have been “eclipsed” by those of men and “erased from history,” in Ramsden’s words.

As most of my readers probably know, I’ve spent the last few years working on a biographical study of Anne Frank. From the start of the project, the idea of writing about Anne’s experience in the camps filled me with trepidation. If Anne made notes about her concentration camp experience, they have been lost. We rely on the limited testimony of others who were with her there, mainly Dutch women who survived, to tell us what happened to her. This testimony has been gone over many times by researchers, starting with Ernst Schnabel, who interviewed some of Anne’s friends and fellow prisoners for his investigation In the Footsteps of Anne Frank (published in English in 1958), but used pseudonyms and other non-journalistic methods. More recently, the Dutch documentary filmmaker Willy Lindwer interviewed those women and others for his film The Last Seven Months of Anne Frank (1988) and also published their testimonies in book form. What could possibly be added?

But as I pored over these books, I found that something was missing: a consideration of Anne’s experience as a woman. Yes, she was only fifteen when she entered Auschwitz, but the Nazis treated her as an adult: she was sent to the women’s division of the camp rather than a children’s barracks and performed the labor demanded of adult women. Starting around mid-1942, women were housed in a sector known as Auschwitz II—Birkenau, several kilometers from the main camp; it was also the site of the gas chambers and crematoria. While they performed labor similar to the men’s, the women were housed in different types of barracks under somewhat different conditions and suffered uniquely female torments, including “sexual victimization, pregnancy, abortion, childbirth,” and more, as Joan Ringelheim, a pioneer in the field of feminist Holocaust studies, described it. The two divisions of the camp were “different horrors within the same Hell,” writes Myrna Goldenberg, another feminist scholar.

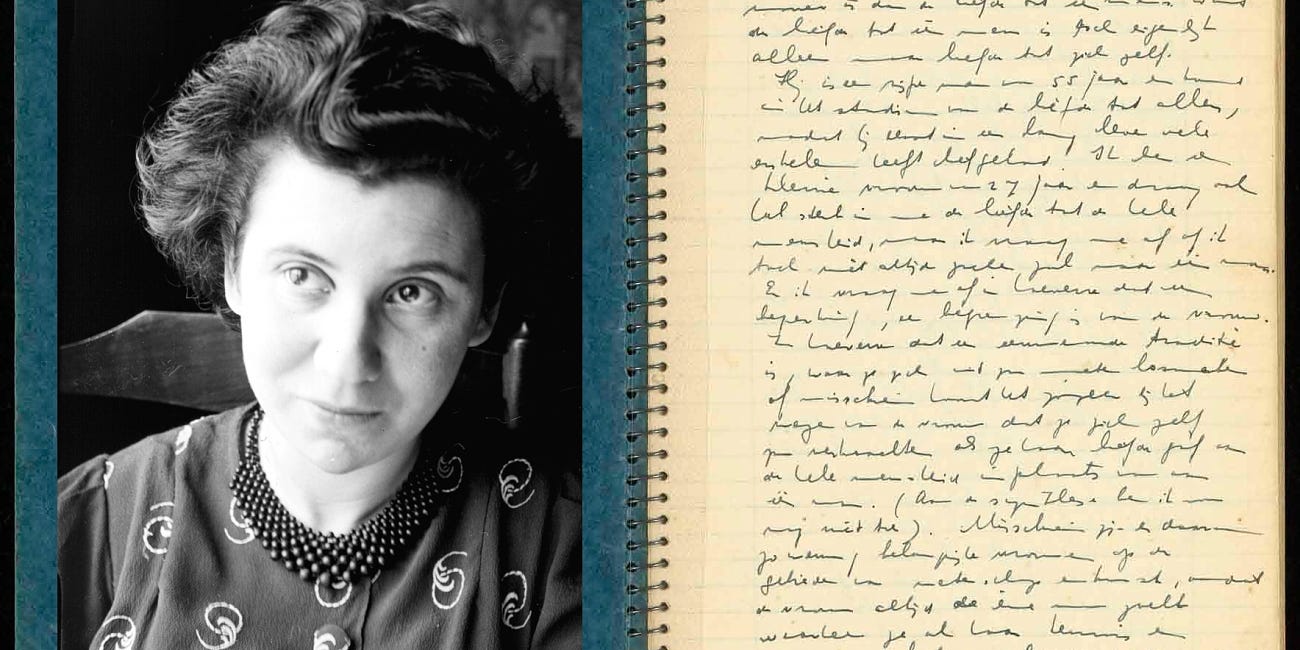

Using Ramsden’s zine as a guide, I began reading testimonies by women, especially those who were in the same places at around the same time as Anne: Olga Lengyel, a Hungarian doctor deported to Auschwitz in 1944; Bertha Ferderber-Salz, a young mother from Poland who also came to the camp that year; Hanna Lévy-Hass, a Yugoslav prisoner who kept a diary in Bergen-Belsen. Even if we can never know about Anne’s inner life during her terrible months in these camps, the experiences of others who were like her, in similar situations, allows for informed speculation about how she might have thought and felt, as I noted in this piece about the Dutch diarist Etty Hillesum, who died in Auschwitz after a period of imprisonment in Westerbork.

One seemingly small difference that had a major impact on female prisoners’ lives was the way they were clothed. In contrast to the men’s striped uniforms, women in the camps were given ordinary clothing—but without regard to its appropriateness for either the setting or the season. Many were forced to wear clothes that were too tight or otherwise revealing. Ferderber-Salz was assigned a light silk dress that would have fit a woman many times larger than she, its neckline plunging to her waist. Her sister was fortunate to receive a long wool dress, but her sister-in-law got a skirt and pajama jacket small enough for a child. Lengyel was given “a formerly elegant [dress] of tulle, quite tattered and transparent, and without a slip…. The dress was open in the front down to the navel and in the back down to the hips.”

All the women’s clothes were marked on the back with red paint—some survivors say a red stripe, others say a red arrow—so that they would be immediately identifiable if they tried to escape. I puzzled over this detail: why red paint? Keren Blankfeld’s new book Lovers in Auschwitz offers an answer. The book is based on Blankfeld’s New York Times article about David Wisnia and Zippi Spitzer, two prisoners who had a romantic relationship in the camp and reconnected much later, but it also gives a detailed look at Auschwitz from Spitzer’s perspective. Her background in graphic design allowed her to gain employment within the Auschwitz bureaucracy, where she used her privilege, grit, and ingenuity to protect herself and others. Among Blankfeld’s discoveries is that it was Spitzer who actually mixed the red paint and applied it to the women’s clothing, which she did with a ruler for maximum precision. Blankfeld and I discussed the experiences of women at Auschwitz during a recent conversation celebrating her book at 92NY; it’s available to watch here.

Like memoirs by men, women’s memoirs tend to emphasize themes of hunger and the struggle to obtain food, as well as the fear of violence—often sexual violence. Their stories of what happened to women who were raped and got pregnant are frankly too harrowing for me to repeat here. But they also stress the importance of social bonding. Women were likely to join together as Lagerschwestern, “camp sisters,” in groups of two or more, which functioned as surrogate families whose members shared food, helped one another acquire necessities, and maintained morale. Giuliana Tedeschi Brunelli, an Italian Jewish prisoner, wrote that life in Birkenau was “like a piece of knitting whose stitches are strong as long as they remain woven together; but if the woolen strand breaks, the invisible stitch that comes undone slips off among the others and is lost.”

In the 1980s, when feminist historians like Ringelheim began their research, some of their colleagues considered the questions they were asking taboo. The eminent Holocaust scholar Lawrence Langer, who sadly passed away last week, argued that if women behaved differently in the camps than men did, it was the result of “situational accident, not gender-driven choice.” Others emphasize that the Nazis persecuted all Jews, without regard to gender difference. This is true. But as Ringelheim wrote, women were “dangerous to the Nazis specifically in their difference from men: in their ability to carry the race.” To ignore the differences in the way they suffered—particularly gender-based suffering like rape—is to ignore “more than half of the Jewish population who were deported or murdered.”

If Anne Frank had survived, she might have published her diary in revised form, as she hoped to do. But she might also have found herself galvanized by her experience in the camps to write a different kind of book: a memoir just as enduring as the ones by Levi and Wiesel that we now consider classics. If she had, our prevailing image of an Auschwitz prisoner might not be of a man in striped pajamas, but a young woman in an ill-fitting dress, inseparable from her mother and her sister, desperate to preserve both her body and her spirit.

Where I’ll be

I’m giving a talk on efforts to censor Anne’s diary at Fordham University next Sunday, February 11, at 3 p.m. The free event includes a tour of the exhibit “Banned! A History of Censorship.” Sign up here.

Israeli/Palestinian reading group

I had a lot going on this month and Grossman’s To the End of the Land turned out to be too much for me. Did anyone else start it? I hope to get to it in the next couple of weeks.

As ever,

Ruth

Very sad to miss your talk next week about a subject that we both care about, but I'm in Israel for a few weeks.

Thanks for a very (sand and) intriguing post!

Objects like clothes tell a story: powerful. As for moving stories of women in the Holocaust, I want to recommend Phyllis Lassner's <Anglo-Jewish Women's Writing and the Holocaust: Displaced Witnesses>(2008) as well as the Jewish Women's Archive.