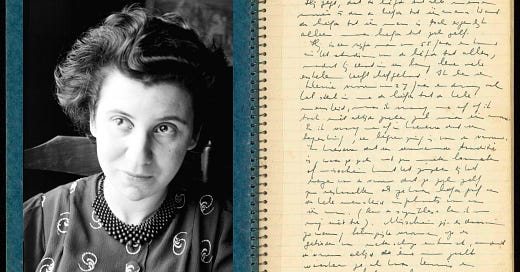

"The chronicler of our adventures"

What Etty Hillesum's diary can—and cannot—tell us about Anne Frank.

Welcome to my new subscribers! I’m glad you’re here. This email comes out once a month. Otherwise, find me on Twitter (still), Instagram, or, if you must, Facebook.

“I shall become the chronicler of our adventures. I shall forge them into a new language and store them inside me should I have no chance to write things down. I shall grow dull and come to l…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ghost Stories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.