Otto Frank: censor or preserver?

The way Anne's father edited her diary is one of the least-understood aspects of her life.

Welcome to my new subscribers! I’m glad you’re here. This email comes out once a month. Otherwise, find me on Twitter (still), Instagram, or, if you must, Facebook.

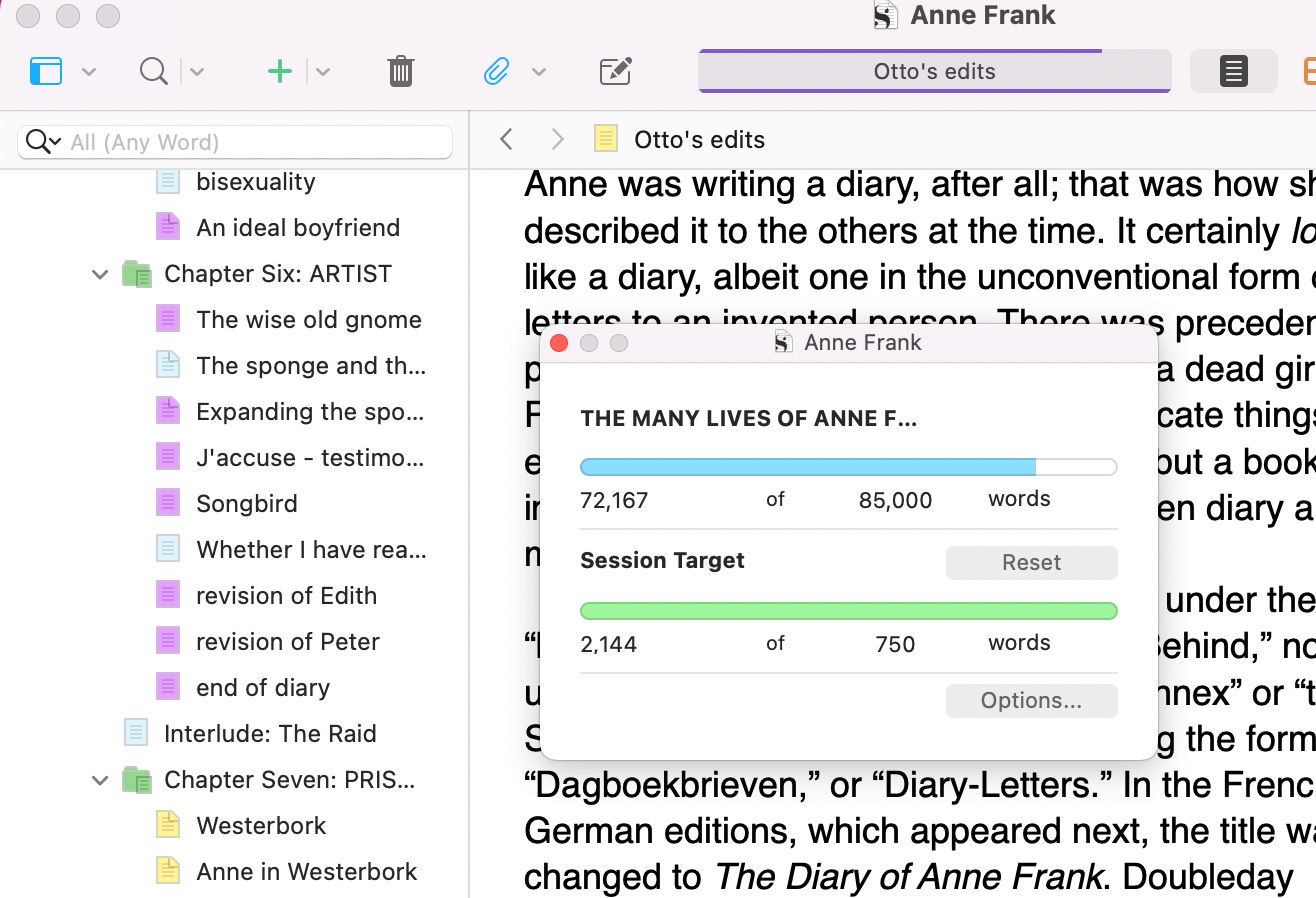

I’m heading towards the finish line on my book about Anne Frank! I took this screenshot on Friday after finishing Chapter 9, about the Diary’s journey to publication in the Netherlands.

The app I’m using is Scrivener, the very best software for longform manuscripts—and no, they don’t pay me to say that! I use it for any writing involving research, including book reviews. Down the left-hand side of the screen, you can see the how the chapters are divided up into sections (Scrivener calls them “Scrivenings,” but that’s where I draw the line). I give them working titles (just for me) and color-code them based on how finished they are—rough draft, revised (after my writing group gives feedback), final—and also based on the type of section. This book includes a number of “meta” sections in which I step outside the main chronology of Anne’s life and try something more experimental; those are the ones in blue.

The section in the body text here focuses on Otto’s edits to Anne’s diary. As those of you who have been here for a while know, I feel strongly that Otto has been unfairly vilified by readers who accuse him of censoring Anne—primarily her thoughts about her changing body, sex, and her mother. Contrary to popular belief, the famous passage in which Anne discussed wanting to touch her best friend’s breasts appears in all versions of the diary published in English. It was cut by the Dutch publisher and restored by Otto personally for the original German and English translations.

Otto also didn’t censor Anne’s criticisms of her mother. There are places where he removed a few words or lines, perhaps because they seemed like overkill when Anne’s overall tenor toward her mother was so negative. But if you go back to the version originally published in English, you’ll find lines like “Just had a big bust-up with Mummy for the umpteenth time; we simply don’t get on together these days,” “Mummy kicked up a frightful row and told Daddy just what she thought of me,” “Mummy and her failings are something I find harder to bear than anything else … I can’t always be drawing attention to her untidiness, her sarcasm, and her lack of sweetness,” and many more.

As I’ve written elsewhere, Otto’s biggest change was to restore Anne’s romance with Peter van Pels—most of which she chose to cut from the version of her diary she intended to publish. His instinct for a good story must have beaten out any qualms he felt about invading his daughter’s privacy regarding her love life.

So what did Otto cut, and why? You’ll have to read the book for the full explanation. But in brief, he did soften some of Anne’s criticism of her mother as well as her nastiest remarks about the Van Pelses, whose cruder personalities and tendency to have screaming fights were completely at odds with the buttoned-up Franks. (I’ve often wondered why neither the Franks nor the Van Pelses anticipated the extent to which their personalities would clash when confined together in such close quarters; the only explanation I can think of is that they never expected to be in hiding for so long.) Otto also toned down Anne’s vitriol toward Fritz Pfeffer, the middle-aged dentist with whom she was forced to share her room, and who—based on her account—doesn’t seem to have liked her any more than she liked him. And Otto changed some elements of her description of him—apparently deciding that the world didn’t need to hear about his interest in discussing his bowels.

“I must work in her sense,” Otto once explained to a journalist. “I decided how to [edit the diary] through thinking how Anne would have done it.” The Anne he was trying to imagine at that point wasn’t identical to the writer of the diary. It was a postwar Anne, an Anne who had survived the war and would be able to decide, with the perspective of time and experience, what she wanted to include in her published diary. It’s easy to see that, after being in Auschwitz together with her mother and in Bergen-Belsen with Mrs. van Pels, she might have come to view them both much differently. (Auschwitz survivors recount stories of Edith Frank’s heroism in protecting her daughters in the camp.) Otto himself had seen Mr. van Pels selected for gassing at Auschwitz. Perhaps he regretted all those fights.

Until I began working on this book, a few years ago, I hadn’t read Anne’s diary in full since I was a teenager. Reading it as an adult, especially as a parent, is an entirely different experience. One of my own children was thirteen when I embarked on this project—the same age as Anne when she started her diary. Children who read Anne’s diary see her as an inspiration, or—as I myself felt as a child and have often heard from others—as a model to whom they can’t possibly live up. But a parent can appreciate the magnitude of what Otto lost and the agony of his task.

What I’m reading

One volume of The Years of Lyndon Johnson down, three to go! I finished The Path to Power and am about to start Volume 2, Means of Ascent. Please join in! (This one is shorter.) It’s been fun sharing my impressions on Twitter—and hearing yours. This week I posted excerpts from a few contemporaneous reviews of the book. Many of them—including in The New York Times Book Review and The Washington Post—were quite harsh. In the NYTBR, Harvard professor David Herbert Donald wrote that Caro was “less a biographer than a hanging judge” and criticized his perceived bias against LBJ and his lack of interest in his subject’s psychology.

Biographers and critics now revere Caro. Have tastes changed that much? If you’ve read Caro—or even if you haven’t!—I’d love to hear what you make of this critical about-face.

Housekeeping

This month marks the one-year anniversary of my move to Substack. I’ve been happy with how easy this platform is to use and the connections I’ve made with other newsletter writers. My newsletter will remain free for now, but complete access to the archives will likely switch to paid at some point.

If you know someone who might be interested in this newsletter—a superfan of the Diary, a teacher who uses it in class—please forward it to them! Your support means a lot to me.

As ever,

Ruth

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are considered, by some, to dream.”—Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House

On Caro, I don’t agree about the first volume. I think it’s a fascinating look at Texas politics but to be evenhanded about it, that could be because I knew very little about Texas before I read the book. As a frequent (although not lately) reader about Lincoln I’d be loath to criticize Donald. From there it goes downhill. In volume 2 he makes LBJ’s opponent the good guy but he was no saint. The one criticism I read (can’t remember where) about volume 3 is that Caro made a relatively minor Civil Rights bill the focus or theme of the book.

Her father changed her diary!!!!! Is that an invasion of her privacy?????